Mujeres Estrellas (Chaco, Argentina) came about based on a question: how can three seemingly conflicting identities (being a woman, Indigenous and Christian) be brought together. Faced with the impossibility asserted by institutions, Mujeres Estrellas seeks to integrate, reflect and offer new interpretations that make the intersection of religion, feminism and ancestry possible. In this “in-between” they have found the right place for their lives and those of many others. They have found the right place for their experiences and backgrounds, living a faith that does not condemn them.

Report: Eloísa Oliva together with Agustina Juárez.

Translation from Spanish: Christina Hamilton

Photographs: Natalia Roca

“I was born into an evangelical family, so I never challenged anything, I never asked any questions, everything they said was just as they said, I accepted it,” Claudia says on this unusually cold morning, in the living room of a house she shares with her four children and her husband on the outskirts of Resistencia, Chaco (Argentina).

“In 2009, I was attending a church where everything was considered a sin: wearing pants was a sin, wearing make-up was a sin, everything was a sin! Wearing earrings or rings other than a wedding band! Then I started to feel like there was something wrong with all of it. They’d say that women were only here to have children and obey their husbands, that we had to keep our heads down, and I said: no, this can’t be, this is violence, it’s psychological violence,” she continues.

“And that’s when a whole process began, one that I feel I went through alone,” her voice cracks as she relives her story. “One day I’ll tell my story without crying, but I don’t think I can yet. Maybe I wasn’t at that church for a long time, but it was very painful for me. I felt very alone; I felt like no one understood me.”

One day, around the time she stopped going to church, the pastor came to her house. Her father had recently died, and she was pregnant with her third daughter. That time, she shared with the pastor everything she had been thinking, and he called her a rebel. Also, because Claudia wanted to have her tubes tied, he warned her that if she proceeded, she would “become a prostitute,” and that she had to have all the children God sent her.

“At the time, I was 27 or 28, so I could’ve gone on to have fifteen children!” Claudia says. She complained to the pastor: “Do you know how we live? Do you know if we have enough to eat, or if we don’t, if there’s food to put on the table for my children? There isn’t, because there’s no work, because their father finds odd jobs, and one can’t afford anything, there’s not enough.”

Other times, a sister from the church would visit her. Claudia asked her to stop visiting, she told her she would lift herself up on her own, and she shared: “Every day when I’m in my room, when my children’s father isn’t here, when my children aren’t here, I sing, because I like to sing. I sing and pray and ask God to give me strength, and I know that the day will come when he’ll tell me ‘today I’ll lift you up’. Because God will never let the righteous be shaken,” she tells us now, with her musical voice.

Today she knows that colonisation and evangelisation cut so deep that she had never even dared to think for herself or ask any questions. She started asking questions as the result of a painful process of feeling expelled, and then everything started to take shape when she began to meet other women.

Mujeres Estrellas

In 2018, Claudia began talking to other people about this process she had been going through “for years here” she says, touching her chest. “That church I was talking about earlier made me stop going, but it didn’t make me stop wanting to go to church,” she says. Talking with her colleagues from the Magdalenas organisation, also from Chaco, she felt supported and met women who had had similar experiences.

In 2019, once she had emerged from her inner pain, Mujeres Estrellas (Women of Stars) was born, Alpi Huaquaañepi in Qom. They took the name from a story that says women descend from the sky. Then they began the task of talking, exchanging experiences and reflecting. “First, we held internal strengthening meetings, either here or at the house of another colleague in Fontana (a town near Resistencia) or somewhere halfway downtown. Over time, several other women joined.”

The group gained strength, especially in 2020, during the pandemic, organising virtual activities. They began to talk about gender violence, abortion and violence in religious settings. It was at that time that Anabella, Claudia’s oldest daughter, who is now at university, joined the group.

Like her mother, Anabella experienced the expulsion that came with asking questions or questioning. And, like her mother, she did not want to abandon her faith. Stopping going to church, she explains, brings feelings of guilt and ambiguity: “I want to go to church, but I feel bad about many issues, like the situation of women; or, if I agree with abortion, it may seem incompatible,” she exemplifies.

Mujeres Estrellas, in response to this sentiment and to integrate points of view and feelings surrounding faith, started organising Bible study groups. They reread the texts to see what they said.

“You have to read, because you go to church and the pastor is there, and he says, ‘Well, this is what the word of God says’. And there are many things that are taken literally. And then you think, ‘But that’s his interpretation, maybe I have a different one. Why is his interpretation valid and mine is not?’” Claudia summarises.

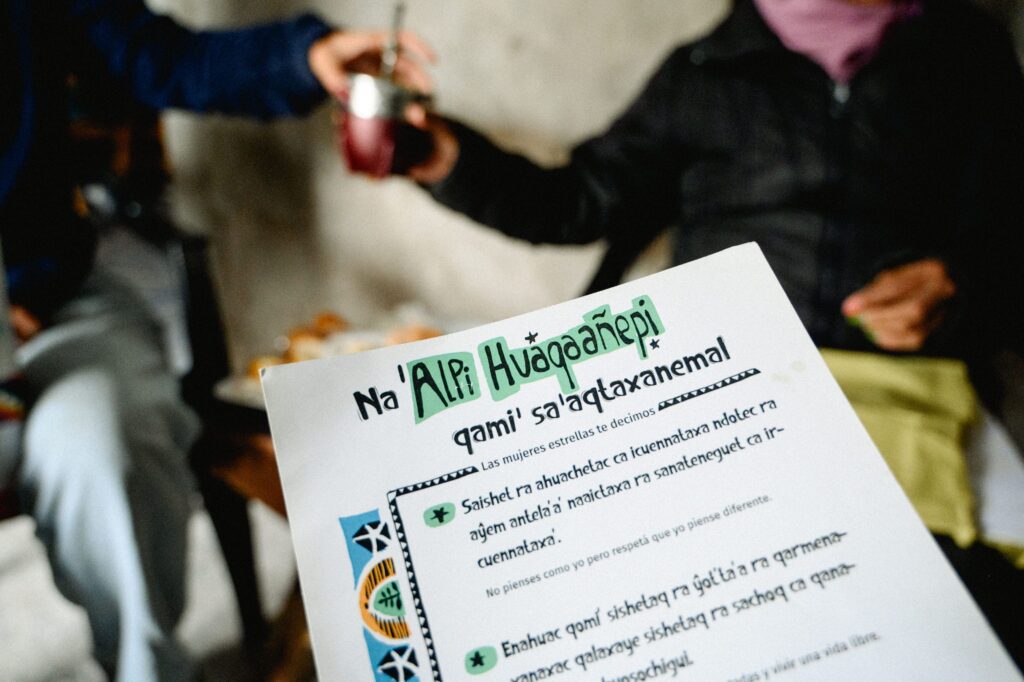

Another of their initiatives was to take an interest in the women in the Bible. They created a pamphlet in which they talk about them, reflecting on their teachings, and they translated the texts into Qom. This was more a strategy to vindicate their language because few people speak Qom today, especially in urban areas.

“I went to church for a long time, and we had our youth meetings, and the premise was always: You have to be like Solomon, like David, like Moses, like Joseph, —all men. And the women? Women were never included. When we began our internal strengthening process, I shared these concerns with the group because it was something I couldn’t ask the leaders of the church I attended,” Anabella says. “So, starting Mujeres Estrellas was like rediscovering the Bible, because until then I had only learned what I was taught in church.”

The group used these pamphlets to get a foot in the door, as conversation starters and as thought-provoking resources. They are brief, well summarised and bilingual. Picking some up, Claudia reads to us: “Here, in Spanish it says, ‘Don’t think like me, but respect that I think differently.’ And here: ‘All of us deserve to be respected and live a free life.’ This one says: ‘We can decide how many children we want to have and when to have them; for that, we have the right to be informed about the methods of care.’ We take the great women of the Bible as a reference, for example Rahab, Sarah, Mary Magdalene and Hagar. And in this last pamphlet, we want to write: ‘It is time to learn new things so that humanity may be awakened and people may treat each other as sisters.’”

Women of Their Time

When the “green tide”1 spread across Argentina, many young women like Anabella were very confused: “At that moment, I felt confused because I felt like I was wrong about Christianity, wrong about my thinking, wrong about everything and I didn’t know how to continue.”

“At first, I was pro-life because the church was pro-life. I thought all that stuff like ‘you’re killing a baby.’ Then I heard a lot of other opinions and brought them to church. I started asking why this or that was wrong, why they said what they said. Because by listening, I was convinced that I shouldn’t interfere in anyone else’s life. For example, before, I didn’t know (because it wasn’t discussed) about clandestine abortions. Well, that’s when I learned that there are a lot of girls who make that decision and for reasons I don’t know. And if they made that decision, it must be for a reason. In church, they started pointing me out as the black sheep, because of the questions I asked.”

Regarding women’s right to health, they say that in some churches, some information is shared, but the problem is at another level. “Some churches teach that women have to take care of themselves, plan their children, when to have them, and everything. But access to healthcare is also important. For example, there are times when contraceptives aren’t available, so that’s another problem, because what do low-income women here do if the public health centre doesn’t have the pill?” Claudia asks. The concern is no small matter: Greater Resistencia is one of the poorest metropolitan areas in Argentina, with a poverty and extreme poverty rate of 76.2 percent2.

Furthermore, Chaco is the province with the largest population of Qom Indigenous people3, plus a large Wichí and Moqoit/Mocoví population. Anabella adds precisely that racial, ethnic-cultural dimension to the issue: “It is said that Qom women, or Indigenous women, do not have abortions because they respect life and so forth. I think it’s a colonising thought, because when you read, you realise that women throughout history say, for example, that they don’t have children ‘so as not to bring them into the world to suffer,’ because the colonisers had arrived and there were massacres, so women had abortions; they preferred not to have children because they knew what awaited them.”

Claudia adds: “We were taught a lot and always told that, for example, when a woman was pregnant, she was looked after carefully, because childbearing also meant respect for her. The husband, for example, couldn’t hunt certain animals. But today, to say that indigenous women don’t have abortions because they respect life wouldn’t be entirely correct. Our grandmothers also talked about abortive plants and natural contraceptives. So I understand that if they show you plants that induce abortions, it’s for a reason.”

As for future projects, Mujeres Estrella plans to organise a retreat to talk and spend time with other women in the area. Another project is to publish a compilation of stories about the experiences of people from the LGBTIQ+ community at churches.

This compilation of stories stems from the experiences of people close to Anabella: the conflict of expulsion and, later, the experience of identity and faith coming into conflict.

Napalpí4 and Ancestral Memory

They are women, they are Christians, they are Indigenous. They work in and navigate educational spaces. Claudia teaches Indigenous Culture and Languages and Anabella is studying Education Sciences. This exemplary environment of normalisation makes them reflect on several things. Just as a pastor once told Claudia that Qom ancestry was “the work of the devil,” in the classroom, Anabella has heard teachers refer to “ignorant Indigenous people” along with conciliatory and inaccurate accounts of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas.

They have also heard outrageous claims that are generalised and attempted to be normalised as “cultural.” For example, the case of sexual abuse of Indigenous girls. “Does it happen? Yes, it happens, like in Creole settings. Are they cultural? No, they are a crime, and they must be reported,” Claudia states clearly.

However, for them, there is always space to made their own and build constructively whether it be in faith, in teaching, and with students. Endlessly pointing fingers, creating awkwardness when necessary. Highlighting the stigmatisations, the absurdities embedded in everyday life. Claudia shares that, for example, her teacher training students sometimes say, “The Indian came out of me,” and she retorts: “What would it be like if I said, ‘The Creole came out of me.’ What are you referring to with that? To the savageness? So, it’s racism. We have to learn to stop using those phrases, to see them from an intercultural perspective, and true interculturality occurs when one doesn’t believe that one’s culture is better or superior to another,” she concludes.

By law, Chaco has an Intercultural Bilingual Education policy, which allows for the recuperation of something lost even among those belonging to the Qom, Moqoit, or Wichi cultures (the three languages incorporated as official languages in the province). “We had already adapted,” they say, “we stopped speaking our language, and now we’re trying to recover some things that can still be recovered.”

Anabella remembers her grandparents referring to people that had endured the education system. “She endured until third grade,” or “she endured a little longer, until sixth grade.” To endure: the imposition of a language, a culture, a way of existing. To endure racism. “I recently realised that they don’t think we are human,” Anabella shares, still shocked by this revelation.

As part of reparation policies, in Chaco, the word Napalpí can no longer be meaningless to anybody. “The court ruling says the massacre must be taught in schools, included in the school curriculum,” Claudia says.

What was it? What is Napalpí? It was a reservation compound located in the north of the province, which was part of a system that confined in forced labour camps the Indigenous population that had survived the extermination campaigns. The Indigenous reservation operated between 1911 and 1956. In July 1924, the Napalpí population was on strike due to the poor living and working conditions. On the 19th of that month, around 100 police officers, military and settlers entered the reservation compound and shot around 400 people. Justice was not served until 98 years later, in May 2022, during a Trial for the Truth.

“Since 2019 I have been teaching at a higher education institute. Everyone was shocked to learn about the massacre because no one knew. When I told them the trial was going to be held, they asked me, “Why if those who did it are no longer here?” “It’s a Trial for the Truth,” I told them, “just like Memory, Truth and Justice, we want that too.” It was a massacre and that has not been given visibility. So there has to be a Trial, because everyone needs to know what happened, and it has to be for the Truth, so that our truth can be told, because the story of the victor has always been told, and they told their version as they pleased,” Claudia shares.

“I strongly believe in the importance of talking about the Napalpí massacre. There were others as well, like the Rincón Bomba massacre in Formosa. Furthermore, in the trial for Napalpí, these crimes were declared crimes against humanity. It’s very important to tell that story, to reclaim it, because it happened,” she adds. To close, she leaves us with this thought: “One of the things that also surprises me a lot is when they say: ‘Your people are very quiet, you are this, you are introverted.’ I answer: Perhaps it has to do with the history we have as a people, as a nation: a history fraught with subjugation, persecution. Something that stuck with me from the story of Melitona Enrique, a survivor of the Napalpí massacre, is that she said that when she was escaping into the bush, her mother told her she had to remain silent, that silence would save her.”

- The Green Tide is the name given to the massive marches and actions in support of Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy (VTP) in Argentina, especially from 2018 until 2020 ↩︎

- https://politikonchaco.com/pobreza-e-indigencia-en-el-gran-resistencia-1-semestre-2024/ ↩︎

- https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/poblacion/censo2022_poblacion_indigena.pdf ↩︎

- Information about Napalpí: https://cenital.com/masacre-de-napalpi-los-cuervos-no-volaron-una-semana/ https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/masacre-de-napalpi-la-justicia-federal-de-chaco-considero-que-se-trato-de-crimenes-de-lesa ↩︎