SinPeCaF is the Union for Domestic Workers in Family Homes in Córdoba (Argentina). They recently turned 60, while celebrating ten years of a historic law: the Special Regime of Employment Contract for Domestic Workers. We talked with them about how the organisation started, their day-to-day activities and the transformation that meeting, getting together and maintaining a shared space implies in the lives and work of women.

Report: Agustina Juárez

Translation: Christina Hamilton

Photos: Natalia Roca

Among photos, notebooks and folders, on each desk in the SinPeCaf office there is a spreadsheet taped to the table. It is a salary scale that establishes the minimum remuneration per hour worked for people who perform cleaning and maintenance work, or non-therapeutic care of children or the elderly.

In Argentina, since 2013, those who do these tasks have had their labour rights recognised, after a long struggle during which unions from all over the country collaborated.

Ana is currently the Secretary General of the union. Sitting in the kitchen, with her colleagues, she tells the story of how she got here. A few years earlier she had replaced her mother at work, because her mother had started to have some health issues. At the time, she did not know that she was being underpaid; Law 26844 establishing the Special Regime of Employment Contract for Domestic Workers, passed in April 2013, was new and not very well known.

Ana sought advice from SinPeCaF and spoke with her employers to change her work conditions. Shortly afterwards, her employers registered her as an employee. She also began to participate regularly in the organisation’s activities.

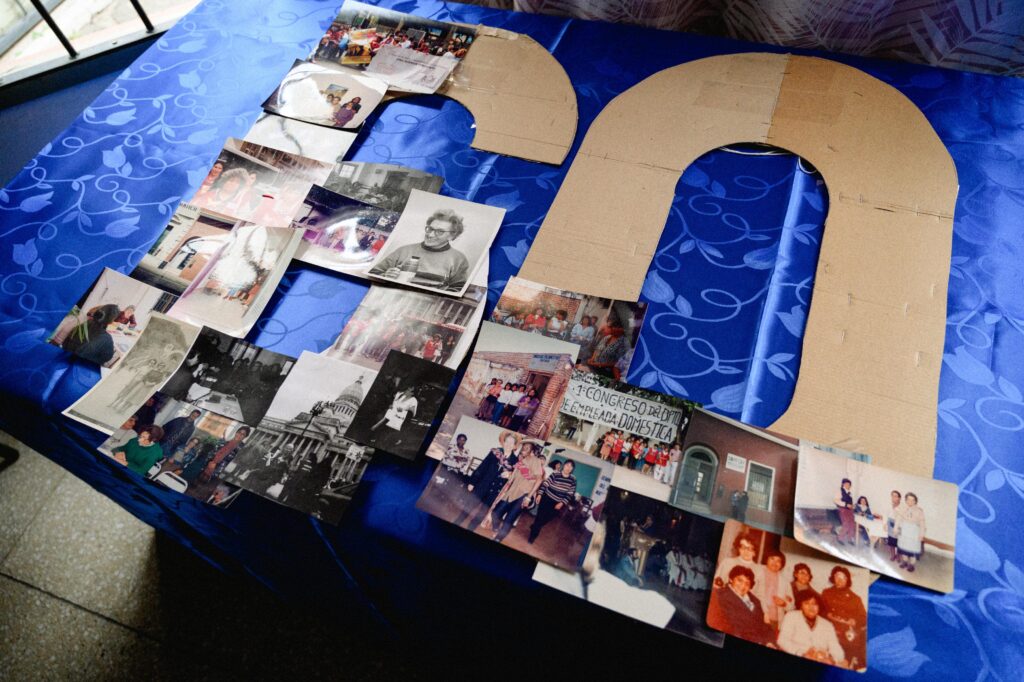

In 2023, in addition to celebrating the first decade of the law, SinPeCaF celebrated 60 years since they started work. We visited them to talk with their current members, learn more about how they are organised and discuss how the organisation was started in 1963 and how it would transform the work of women in Córdoba.

It is not something we make up, it is a law

In Argentina, as in other countries in the region, talking about paid domestic work means talking about one of the most common jobs amongst women. It is estimated that one in eight employed women is a domestic worker; fundamentally, women from grassroots sectors1.

Law 26844 establishing the Special Regime of Employment Contract for Domestic Workers was an important step towards expanding labour rights mainly for this sector of women. By leaving behind the old Domestic Service Regime, sanctioned in 1956, the new law introduced a new paradigm: the possibility of referring to work and workers, instead of services and service personnel2.

In this way, labour rights such as paid holidays, bonuses, maternity leaves, severance pay, occupational hazard insurance and having pension contributions for their future (among other rights) began to be recognised, putting the sector on equal footing with other male and female workers.

For Sonia, Deputy Secretary General of SinPeCaf, the main change that the law brought about was having legal support that did not exist previously. “Regardless of what an employer wants to pay, whether or not they want to give you paid holidays – there is legal back up to support us. It is not something that we make up or even a union makes up, it is a law”, says Sonia. And she insists: it is a change that she herself experienced as a worker, and that she also saw change in her colleagues’ experiences.

One of the union members brings up the time she had to discuss the issue of holidays with her employers. They went away on a trip and left her in charge of the house in their absence. When they returned, they deducted those days from her holidays. She had to clarify to them that those days did not count as part of her annual leave, that holidays involve additional holiday pay: it is free time and one can decide what to do with it.

“And this didn’t happen that long ago,” she adds, despite the fact that she has worked in the same house for more than twenty years. “And do you know why we have to go through that? Due to lack of information,” she concludes.

SinPeCaf works to change this lack of information: socialising and raising awareness, so that all workers know their rights and exercise them, just as those who today make up the organisation did, by seeking advice from the union.

A union made for and by women workers

“Are you sure he’s not the owner of the house?” they ask, from the corner of the table. “No, we already talked to him. He works there,” they respond from the other side. The conversation is a little unusual hence the surprise. If women represent almost all of the workers in the sector, SinPeCaf’s records reflect this: there are 15,000 members, only 40 are men.

Ana tells of some recent cases that stood out for her: men who, instead of being registered in the categories corresponding to their jobs, they were registered in lower-paid categories, such as General Tasks, which includes cleaning work and other home maintenance activities.

“It is the task itself that makes your job precarious,” Ana states, to understand this phenomenon that she will identify as the cultural factor. That factor that is linked to recognising some tasks as better than others, and where those related to cleaning, care tasks and preparing food are considered less valuable compared to other tasks that are carried out, even within homes.

According to data from the 2021 National Time Use Survey, from the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC), on average, people dedicate 5 hours and 18 minutes a day to care tasks. Even though these tasks are distributed, there are inequalities in their distribution: women dedicate at least 6:30 hours to these tasks, compared to 3:40 for their male peers. A difference that increases further in homes with children or people under their care.

When it comes to paid care work, this gap takes on another dimension: the lack of recognition is combined with job insecurity. Although it has been ten years since the law was passed, in Argentina, around 75% of female workers in the sector do so in informal conditions3.

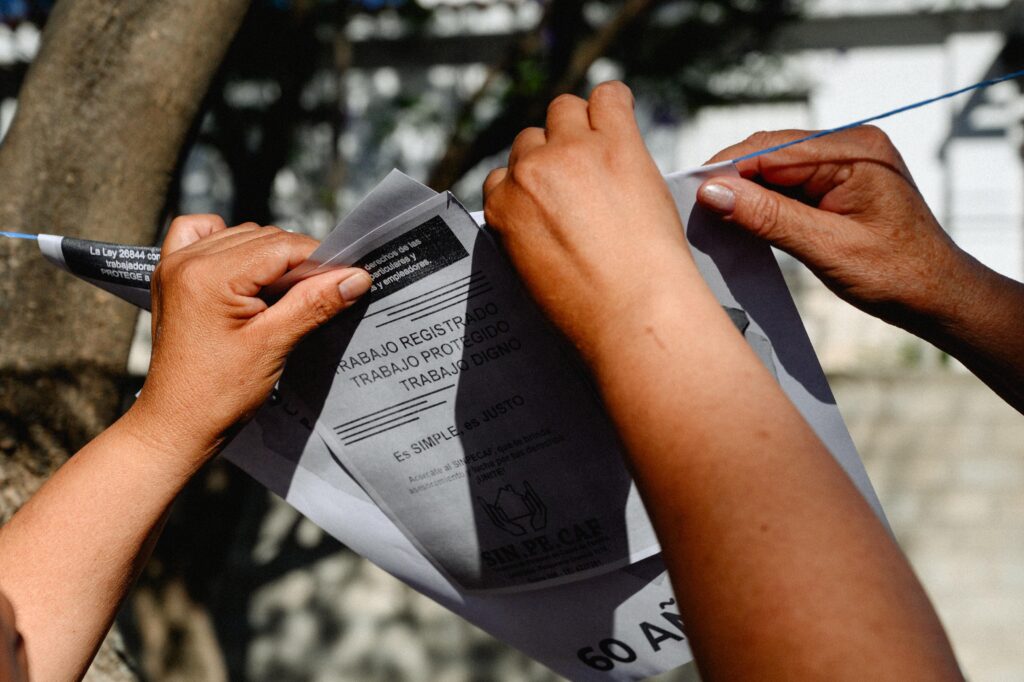

SinPeCaf is running the campaign ¡Registrame! (which means Register me!) and works as a double call to action. On the one hand, it is aimed at employers to formally register their employees and on the other, to society in general, to recognise care work as an essential part for the reproduction and maintenance of life.

For SinPeCaf members, a comprehensive perspective of care implies recognising that those who provide paid care are also those who care within their homes. The law is a baseline from which to start: “We want it to be understood that the work we do is work done by women, mainly, and that they are also the main caregivers for their families,” adds Ana.

“It is a challenge that we face every day: we seek to make things easier.”

“Often employers think they are paying everything accordingly, the workers too, and it turns out that, down the track they discover that they have outstanding payments. This comes to light once they retire,” says Lourdes, a lawyer and daughter of a SinPeCaf member.

Lourdes, the Doc, as she is known in the organisation, volunteers on Tuesdays and Thursdays in the office. She is in charge of explaining to the workers how the pension system works, reviewing their work history and helping them to keep their social contributions up to date – which are all done online.

Listening attentively on the other side of the desk to help the women reopen their email account, learn to send an email, obtain paperwork from their health insurance, since 2023, computer classes have been added to SinPeCaf activities.

A school for adults also operates out of their office, along with other training workshops, such as the garment-making workshop, led by Sonia, or the cooking workshop, led by Rosa, another member of the organisation. “We want to add healthy food, specific food for diabetic and coeliac people,” she says.

The workshops seek to professionalise the practical skills the workers have and organise the knowledge they have. A challenge that they take on every day. In line with this, Ana brings up another point that becomes fundamental for the exercise of rights: self-esteem.

“I always say that we have to do workshops that strengthen our self-esteem. Talk about and discuss why it is so hard for us to understand that we have rights. That is part of what we do at the union: work to strengthen that in each worker.”

Know where we come from to know where we are going

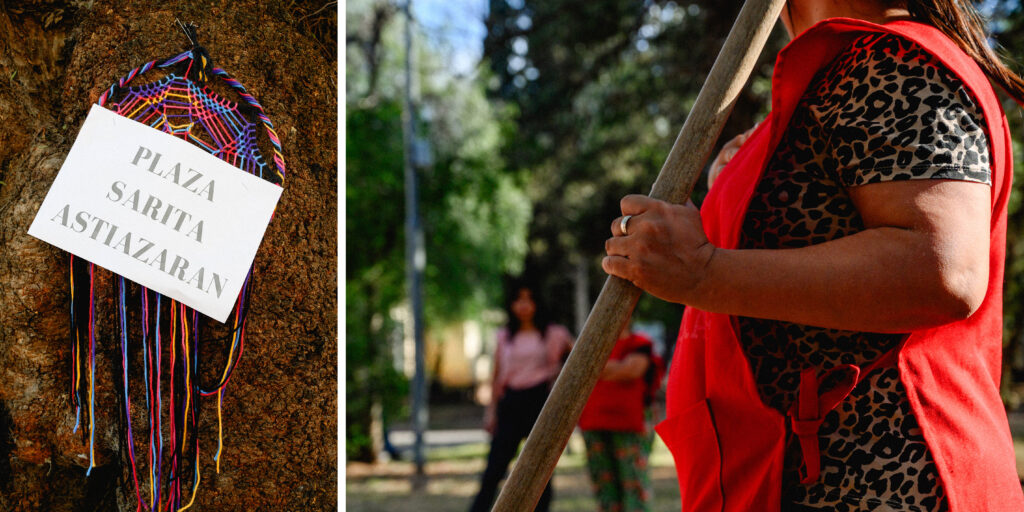

For their 60th anniversary, SinPeCaf prepared two celebrations. The first, in Colinas de Velez Sarsfield neighbourhood, in the southern part of the city of Córdoba, in a park that bears the name of one of its founders, Sara Astiazarán. The second celebration was held in the office. They paid tribute to the founders and members of the union since its outset: Hilda Burgos, Norma Figueroa, Blanca Gorosito, Flora Quintero. There was also time to get together, dance, celebrate: it is not every day a union turns 60.

Bunting and posters were hung in the neighbourhood park. They brought pots with flowers ready to be transplanted and set up a flower bed. “We came to add colour to the park” they summarise. It is a way to keep the memory of Sara alive, tell her story and share how the union came about.

SinPeCaf was founded in 1963 by a group of women workers among whom was Sarita, as she was known. Sarita had started working in a family home in the same neighbourhood where today the park is that bears her name.

By then, Sara had stopped participating in the congregation where she was a nun. Living in the Bella Vista neighbourhood in Córdoba, she met other domestic workers like herself.

Sarita wanted to know what the working conditions were like in each house and she began talking to the workers while they were waiting for the bus to come and go from work. That was how she started learning about the conditions of exploitation and thinking of a union organisation that could represent them.

Shortly after, Sara was fired. SinPeCaf members say that her being fired was related to Sara eating a slice of cake from an event that her employer had organised. Upon finding out about it, her employer decided to fire her, not knowing that, for Sara and other women workers, this event would be the catalyst for her to advance her dignity and rights.

In 1969, with Sara’s participation, SinPeCaf played a special role in the Cordobazo, one of the most transcendental political events in Argentine history. The general strike crystallised the rejection of the economic and social policies of the dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía (1966 – 1970) in a massive protest organised for May 29 and 30.

Sara not only participated in the congress of the General Confederation of Labour (CGT) together with other representatives of unions and guilds, but with her vote she broke the tie in the vote that declared the active strike and the mobilisation to take place on the streets of Córdoba.

Just a few years ago, a group of local female historians and researchers gave visibility to the participation of Sara and other women union members, which had been erased from the historical event4.

Wrapping up our discussions, we asked ourselves: Is it possible to summarise 60 years of work? Ana tries saying: “We all came looking to have some right recognised that had been denied us. And we all fell in love with this place, that is why we do what we do.”

- “Ecofeminita. (2022). Ecofeminita/EcoFemiData: informes ecofemidata. (Ecofeminita/EcoFemiData: ecofemidata reports) Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4540185” ↩︎

- https://radiografica.org.ar/2023/04/08/a-una-decada-del-nuevo-regimen-de-contrato-de-trabajo-para-el-personal-de-casas-particulares/ ↩︎

- Dirección de Mapeo Federal del Cuidado en base a EPH II Trimestre de 2022, INDEC. (Federal Care Mapping Directorate based on Permanent Household Survey II Quarter of 2022, INDEC.) ↩︎

- https://historiaobrera.com.ar/cpt_mitin/de-cordobesas-en-epocas-de-cordobazos/ ↩︎